By Robert Snell, Certified Financial Planner and Housing Affordability Expert.

Sometime ago, I can’t pin point when it actually happened, politicians, analysts and journalists changed the way they reported on housing affordability statistics. Since then it’s hard to find any commentator who believe young Australians aren’t facing a housing affordability crisis.

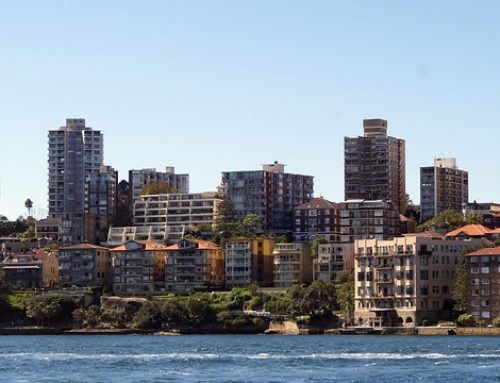

At its most basic measure, housing affordability can be determined by the median home price in a city, for example Sydney and income.

The median house price (the middle house price from lowest to highest prices, when placed in order), provides a reasonable indicator as to where the price is. Given the simplistic nature of the median, it’s hard to fudge or muddle with this figure, given that the data is freely available.

Income is the other measure that it used to assess home affordability. And it’s the reporting on income that’s become a REAL PROBLEM for most analysts, commentators and journalists.

Once upon a time in Australia’s past, a typical Australian family had one income. Gender issues aside, it was usually the father, with the mother staying home to raise the kids. Then one day, the good intentioned boffins who measure things for a living decided that household income would be a better measure –probably to reflect the changing nature of the workforce no doubt.

What those same statisticians haven’t realised though is that what once might have been a two income household, now might be a four or more income household, as the kids have grown up and can’t afford to move out of home given housing affordability issues.

So when commentators like CoreData report the cost of buying a dwelling currently takes 7.2 times a typical household income1 they’re not actually telling an untruth, but they aren’t talking about the purchasing power of an individual.

So what does this mean?

Without a doubt household income is going to be higher than a single income. This means the 7.2 times measure is really over 12 times2 for a person living in Sydney.

It also matters because households have changed again. Many young Australians are living at home into adult hood or in share house situations because they can’t afford to buy or rent by themselves. So this idea of household income actually counts these arrangements where the parties while under the same roof, don’t necessarily share goals. Therefore I don’t believe that household is the correct measure.

So why does this matter?

In simple terms it matters because the statistics are skewed and don’t show how bad home affordability really is. And it matters for several reasons:

- It’s covering the problem up for young Australians, who are typically on lower single incomes.

- It’s not reflective for young people in an Apprenticeship, studying at University or TAFE or starting their first job while living at home or in a share house.

- It’s gender biased for single females, who typically earn less than their male counterparts.

- It’s doesn’t reflect the nature of many single parent households who are working and raising kids

- It’s just plain wrong for many in our community who work part time and are affected by the increasing ‘casualisation’ of the workforce

- It’s also wrong for many older Australians who are on fixed incomes.

All of the above segments of our community aren’t represented by an average household income measure. All of these segments however are the ones most affected by Australia’s housing affordability crisis.

So what should commentators do?

We need to use the international measure for home affordability offered by Demographia which uses a single income measure3 – not a household income measures.

According to Demographia, anything above 3 times starts to become unaffordable4.

It’s also important to get some truth back into home affordability statistics. It might help those in Government see the real nature of the problem and force them to address our housing affordability crisis.

We also should demand a wider set of housing affordability statistics

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports every May and November on Average Weekly Earnings for every State and Territory in Australia by Gender.5 We also have data on the types of homes being sold – houses or apartments and the number of bedrooms they have.

I believe that in this ‘age of information’ it’s not an unrealistic request for analysts to report on a more comprehensive set of housing affordability statistics. This will enable our governments at all levels and locations to gain a more insightful understanding who is and which locations are most affected. Without more meaningful information our governments are less likely to be held to account to implement more sophisticated solutions to the home affordability crisis.

References:

1. Perceptions of Housing Affordability Report – Corelogic

2,3, 4. The 13th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2017 – Demographia

5. ABS Reference 6302.0 – Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, November 2016 – Australian Bureau of Statistics.